Apr 25, 2013

Undertaker’s Invention Revolutionizes the Telephone

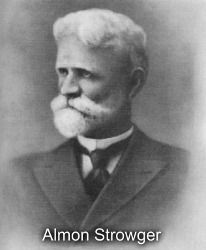

It was in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1888, when Almon B. Strowger stormed through the door of his undertaking parlor and slammed the door behind him. To say that Strowger was furious would have been an understatement, but on this particular day, he had just learned that a customer had tried to telephone him, only to be told by a Central operator that the line was busy.

Busy?

Busy!

His line had not been busy — he was sure of it, but there was nothing he could do to prove otherwise. How could he, this was the age of switchboard operators. There were no monthly bill statements with lists upon lists of outgoing and incoming calls.

It was too late for him now. The damage was done and he lost some business, and no matter how much he protested and complained, he could not recapture the customer’s call. But this wasn’t the first time he was sure he’d lost a customer. Whether it was by some honest error on the Central operator’s part or a devious scheme concocted by a competitor, Strowger had decided, enough was enough. For too long he had been losing clients to a competitor whose telephone-operator wife was intercepting and redirecting every one of his calls. No longer would he be the victim of another missed opportunity.

It had been over ten years since Alexander Graham Bell first transmitted speech electrically with an order to his assistant Thomas A. Watson. Since then, the telephone industry only grew faster and faster in America’s larger cities, but as they grew, so did they become more and more complex with telephone central offices. Switchboards soon dominated the way communication was transmitted, and to ensure smooth activity, many operators would sit in long rows, plugging countless plugs into countless jacks.

Strowger considered this as he stared at the wall telephone. He wasn’t by any means an engineer. At an early age, he became a teacher for the Penfield Elementary School, where he had attended as a child. In 1861, he became a volunteer in the army to participate in the Civil War. However, with the growth of the funeral industry, he soon settled into Kansas City, Missouri between 1886 to operate his own funeral parlor. So what did he know of telephone operation?

He knew that a manual switchboard servicing 100 subscribers had 10 rows of individual lines, which meant if a call were placed for telephone number 75, the operator would move the plug to the seventh row, then insert it into the fifth terminal of that row. He further knew that there had been continuous accomplishments with the control of electricity, including that of electromagnets, which controlled variations of an electrical current passing through a wire varying between strong and weak.

That’s when a thought came to mind – what if the telephone switchboard operation could automatically direct a call using electrical force, provided an electromechanical device could seek out its desired line according to the number of pulses sent to it.

Strowger spent days thinking through his problem in his Kansas City undertaking parlor. He may not have had the engineering degree that others had, but one thing the former school teacher had was an inquisitive neophyte’s mind, which allowed him the ability to plot a simple, straightforward path through a world of complex engineering designs.

That’s when he was suddenly struck with an idea – what if a metal finger was made to react to impulses sent by a calling party through electrical force from one terminal to another, both vertically and horizontally, acting as a switchboard contact between two telephone lines. Strowger figured this would allow the impulses to count the number of contacts the way a switchboard operator would.

Rummaging around, Strowger found a round cardboard collar box and laid it on his desk. Using straight pins, he stuck them around the box in 10 rows of neat until 100 pins protruded slightly around the inside circumference of the box – this was his circular switchboard, with each pin representing an individual telephone. He then imagined a shaft protruding through the centre with a metal finger attached, which would move either up or down as well as horizontally along any given row, representing the operator’s arm.

It wasn’t long before Strowger enlisted the help of an electrician to arrange some magnets and other electrical equipment into a device to test out his metal finger principle. He knew that if his device worked, he wouldn’t need the assistance of an operator, and over the next several months, the businessman-turned-inventor worked on his idea, refining it into a workable model before filing his first patent on March 2, 1889.

However, the Strowger device would not be met with praise right away. Two years after the patent was granted, Strowger found himself faced with a market that had little interest in his device. Businessmen were skeptical that the contraption would actually work. That was, until an enterprising salesman known as Joseph Harris persuaded Strowger to relocate to Chicago where they arranged to have several model switches built by a novelty company using the Strowger schematics.

To help them stand out more, the Strowger Automatic Telephone Company was born on 1891, and a year later, the automatic system was given its first public trial, where it would quickly be met with praise.

Strowger’s invention quickly signalled a new era in the telephone industry, brought on by a mood of bitter resentment over the loss of clients to a competitor. Since that day, his creation has become the second greatest landmark in the history of modern telephones, influencing engineers to introduce automatic intermittent ringing; automatic busy tones; instantaneous ring cut-off when the phone is pulled from the receiver; and revertive ring tones, which allows callers to hear the ringing of the telephone at the other end. The Strowger switches were used until the late 1970s until touch-tone dialling was introduced.

Click here to view original post.

ASD is honored to publish this guest blog post by Matthew Gillies, a writer on MySendOff.com, the world’s largest life celebration Information Library. MySendOff is the only social media site that brings together pre-planning consumers and funeral professionals with articles that illuminate the rich history of the funeral professional and explore unique ways to memorialize a life. Whether you want to read about history, culture, or miraculous events, MySendOff.com has a story that will pique your interest.

ASD is honored to publish this guest blog post by Matthew Gillies, a writer on MySendOff.com, the world’s largest life celebration Information Library. MySendOff is the only social media site that brings together pre-planning consumers and funeral professionals with articles that illuminate the rich history of the funeral professional and explore unique ways to memorialize a life. Whether you want to read about history, culture, or miraculous events, MySendOff.com has a story that will pique your interest.

About The Author

Jess Farren (Fowler)

Jess Farren (Fowler) is a Public Relations Specialist and Staff Writer who has been a part of the ASD team since 2003. Jess manages ASD’s company blog and has been published in several funeral trade magazines. She has written articles on a variety of subjects including communication, business planning, technology, marketing and funeral trends. You can contact Jess directly at Jess@myASD.com